“As we neared the Place we saw on the

opposite side of the street two flickering iron lanterns that threw a ghastly

green light down upon the barred dead-black shutters of the building, and

caught the faces of the passers-by with sickly rays that took out all the life

and transformed them into the semblance of corpses. Across the top of the

closed black entrance were large white letters, reading simply:

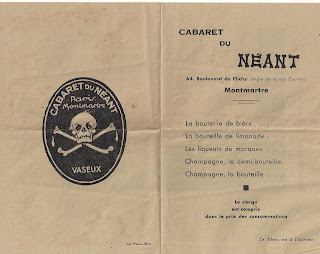

CAFE DU NEANT

The entrance was

heavily draped with black cerements, having white trimmings, such as hang

before the houses of the dead in Paris.

Here patrolled a solitary croque-mort, or hired pall-bearer, his black cape

drawn closely about him, the green light reflected by his glazed top-hat. A

more dismal and forbidding place it would be difficult to imagine. Mr. Thompkins

paled a little when he discovered that this was our destination, this grisly

caricature of eternal nothingness, and hesitated at the threshold. Without a

word Bishop firmly took his arm and entered. The lonely croque-mort drew apart

the heavy curtain and admitted us into a black hole that proved later to be a

room. The chamber was dimly lighted with wax tapers, and a large chandelier

intricately devised of human skulls and arms, with funeral candles held in

their fleshless fingers, gave its small quota of light.

Large, heavy,

wooden coffins, resting on biers, were ranged about the room in an order

suggesting the recent happening of a frightful catastrophe. The walls were

decorated with skulls and bones, skeletons in grotesque attitudes, battle-pictures,

and guillotines in action. Death, carnage, assassination were the dominant

note, set in black hangings and illuminated with mottoes on death. A half-dozen

voices droned this in a low monotone: "Enter, mortals of this sinful

world, enter into the mists and shadows of eternity. Select your biers, to the

right, to the left; fit yourselves comfortably to them, and repose in the

solemnity and tranquillity of death; and may God have mercy on your souls!"

A number of

persons who had preceded us had already pre-empted their coffins, and were

sitting beside them awaiting developments and enjoying their consommations,

using the coffins for their real purpose, tables for holding drinking-glasses. Alongside

the glasses were slender tapers by which the visitors might see one another.

There seemed to be

no mechanical imperfection in the illusion of a charnel-house; we imagined that

even chemistry had contributed its resources, for there seemed distinctly to be

the odor appropriate to such a place. We found a vacant coffin in the vault,

seated ourselves at it on rush-bottomed stools, and awaited further

developments.

Another croque-mort

a garcon he was came up through the gloom to take our orders. He was dressed

completely in the professional garb of a hearse-follower, including claw-hammer

coat, full-dress front, glazed tile, and oval silver badge. He droned, "Bon

soir, Macchabees! [This word (also Maccabe, argot Macabit) is given in Paris

by sailors to cadavers found floating in the river] Buvez les crachats

d'asthmatiques, voila des sueurs froides d'agonisants. Prenez done des certificats de deces, seulement

vingt sous. C'est pas cher et c'est artistique !"

Bishop said that he would be pleased

with a lowly bock. Mr. Thompkins

chose cherries a l'eau-de-vie, and I, une menthe.

"One microbe of Asiatic cholera

from the last corpse, one leg of a lively cancer, and one sample of our

consumption germ!" moaned the creature toward a black hole at the farther

end of the room. Some women among the visitors tittered, others shuddered, and

Mr. Thompkins broke out in a cold sweat on his brow, while a curious

accompaniment of anger shone in his eyes. Our sleepy pallbearer soon loomed

through the darkness with our deadly microbes, and waked the echoes in the

hollow casket upon which he set the glasses with a thump.

"Drink,

Macchabees!" he wailed: "drink these noxious potions, which contain

thvilest and deadliest poisons!"

"The villain!"

gasped Mr. Thompkins; "it is horrible, disgusting, filthy!"

The tapers

flickered feebly on the coffins, and the white skulls grinned at him mockingly

from their sable background. Bishop exhausted all his tactics in trying to

induce Mr. Thompkins to taste his brandied cherries, but that gentleman

positively refused, he seemed unable to banish the idea that they were laden

with disease germs.

After we had been

seated here for some time, getting no consolation from the utter absence of

spirit and levity among the other guests, and enjoying only the dismay and

trepidation of new and strange arrivals, a rather good-looking young fellow,

dressed in a black clerical coat, came through a dark door and began to address

the assembled patrons. His voice was smooth, his manner solemn and impressive,

as he delivered a well-worded discourse on death. He spoke of it as the gate

through which we must all make our exit from this world, of the gloom, the

loneliness, the utter sense of helplessness and desolation. As he warmed to his

subject he enlarged upon the follies that hasten the advent of death, and spoke

of the relentless certainty and the incredible variety of ways in which the

reaper claims his victims. Then he passed on to the terrors of actual

dissolution, the tortures of the body, the rending of the soul, the

unimaginable agonies that sensibilities rendered acutely susceptible at this

extremity are called upon to endure. It required good nerves to listen to that,

for the man was perfect in his role. From matters of individual interest in

death he passed to death in its larger aspects. He pointed to a large and

striking battle scene, in which the combatants had come to hand-to-hand

fighting, and were butchering one another in a mad lust for blood. Suddenly the

picture began to glow, the light bringing out its ghastly details with hideous

distinctness. Then as suddenly it faded away, and where fighting men had been

there were skeletons writhing and struggling in a deadly embrace. A similar

effect was produced with a painting giving a wonderfully realistic

representation of an execution by the guillotine. The bleeding trunk of the

victim lying upon the flap-board dissolved, the flesh slowly disappearing,

leaving only the white bones. Another picture, representing a brilliant dance-hall

filled with happy revellers, slowly merged into a grotesque dance of skeletons;

and thus it was with the other pictures about the room.

All this being

done, the master of ceremonies, in lugubrious tones, invited us to enter the

chambre de la mort. All the visitors rose, and, bearing each a taper, passed in

single file into a narrow, dark passage faintly illuminated with sickly green

lights, the young man in clerical garb acting as pilot. The cross effects of

green and yellow lights on the faces of the groping procession were more

startling than picturesque. The way was lined with bones, skulls, and fragments

of human bodies.

"O

Macchabees, nous sommes devant la porte

de la chambre de la mort!" wailed an unearthly voice from the farther end

of the passage as we advanced. Then before us appeared a solitary figure standing

beneath a green lamp. The figure was completely shrouded in black, only the

eyes being visible, and they shone through holes in the pointed cowl. From the

folds of the gown it brought forth a massive iron key attached to a chain, and,

approaching a door seemingly made of iron and heavily studded with spikes and

crossed with bars, inserted and turned the key; the bolts moved with a harsh,

grating noise, and the door of the chamber of death swung slowly open.

"O

Macchabees, enter into eternity, whence none ever return!" cried the new,

strange voice.

The walls of the

room were a dead and unrelieved black. At one side two tall candles were

burning, but their feeble light was insufficient even to disclose the presence

of the black walls of the chamber or indicate that anything but unending

blackness extended heavenward. There was not a thing to catch and reflect a

single ray of the light and thus become visible in the blackness.

Between the two

candles was an upright opening in the wall; it was of the shape of a coffin. We

were seated upon rows of small black caskets resting on the floor in front of

the candles. There was hardly a whisper among the visitors. The black-hooded

figure passed silently out of view and vanished in the darkness.

Presently a pale, greenish-white illumination

began to light up the coffin-shaped hole in the wall, clearly marking its

outline against the black. Within this space there stood a coffin upright, in

which a pretty young woman, robed in a white shroud, fitted snugly. Soon it was

evident that she was very much alive, for she smiled and looked at us saucily. But

that was not for long. From the depths came a dismal wail: "O Macchabee,

beautiful, breathing mortal, pulsating with the warmth and richness of life, thou

art now in the grasp of death! Compose thy soul for the end!"

Her face slowly

became white and rigid; her eyes sank; her lips tightened across her teeth; her

cheeks took on the hollowness of death, she was dead. But it did not end with

that. From white the face slowly grew livid... then purplish black... The eyes

visibly shrank into their greenish-yellow sockets... Slowly the hair fell away...

The nose melted away into a purple putrid spot. The whole face became a semi-liquid

mass of corruption. Presently all this had disappeared, and a gleaming skull

shone where so recently had been the handsome face of a woman; naked teeth

grinned inanely and savagely where rosy lips had so recently smiled. Even the

shroud had gradually disappeared, and an entire skeleton stood revealed in the

coffin. The wail again rang through the silent vault: "Ah, ah, Macchabee! Thou

hast reached the last stage of dissolution, so dreadful to mortals. The work

that follows death is complete. But despair not, for death is not the end of

all. The power is given to those who merit it, not only to return to life, but

to return in any form and station preferred to the old. So return if thou

deservedst and desirest."

With a slowness

equal to that of the dissolution, the bones became covered with flesh and

cerements, and all the ghastly steps were reproduced reversed. Gradually the

sparkle of the eyes began to shine through the gloom; but when the reformation

was completed, behold! there was no longer the handsome and smiling young

woman, but the sleek, rotund body, ruddy cheeks, and self-conscious look of a

banker. It was not until this touch of comedy relieved the strain that the

rigidity with which Mr. Thompkins had sat between us began to relax, and a

smile played over his face, a bewildered, but none the less a pleasant, smile. The

prosperous banker stepped forth, sleek and tangible, and haughtily strode away

before our eyes, passing through the audience into the darkness. Again was the

coffin-shaped hole in the wall dark and empty.

He of the black

gown and pointed hood now emerged through an invisible door, and asked if there

was any one in the audience who desired to pass through the experience that

they had just witnessed. This created a suppressed commotion; each peered into

the face of his neighbor to find one with courage sufficient for the ordeal. Bishop

suggested to Mr. Thompkins in a whisper that he submit himself, but that

gentleman very peremptorily declined. Then, after a pause, Bishop stepped forth

and announced that he was prepared to die. He was asked solemnly by the doleful

person if he was ready to accept all the consequences of his decision. He

replied that he was. Then he disappeared through the black wall, and presently

appeared in the greenish-white light of the open coffin. There he composed

himself as he imagined a corpse ought, crossed his hands upon his breast,

suffered the white shroud to be drawn about him, and awaited results, after he

had made a rueful grimace that threw the first gleam of suppressed merriment

through the oppressed audience. He passed through all the ghastly stages that

the former occupant of the coffin had experienced, and returned in proper

person to life and to his seat beside Mr. Thompkins, the audience applauding

softly.

A mysterious figure in black

waylaid the crowd as it filed out. He held an inverted skull, into which we

were expected to drop sous through the natural opening there, and it was with

the feeling of relief from a heavy weight that we departed and turned our backs

on the green lights at the entrance”.

What a wonderful contrast ! Here

we were in the free, wide, noisy, brilliant world again. Here again were the

crowds, the venders, saucy grisettes with their bright smiles, shining teeth,

and alluring glances. Here again were the bustling cafes, the music, the lights,

the life, and above all the giant arms of the Moulin Rouge sweeping the sky.

"Now," quietly remarked

Bishop, ••having passed through death, we will explore hell”…

William Chambers Morrow,

Bohemian Paris of To-day (1899)